Two mortal sins in wine branding

Two mortal sins in wine branding

By Geordie Clarke / Contributing Editor

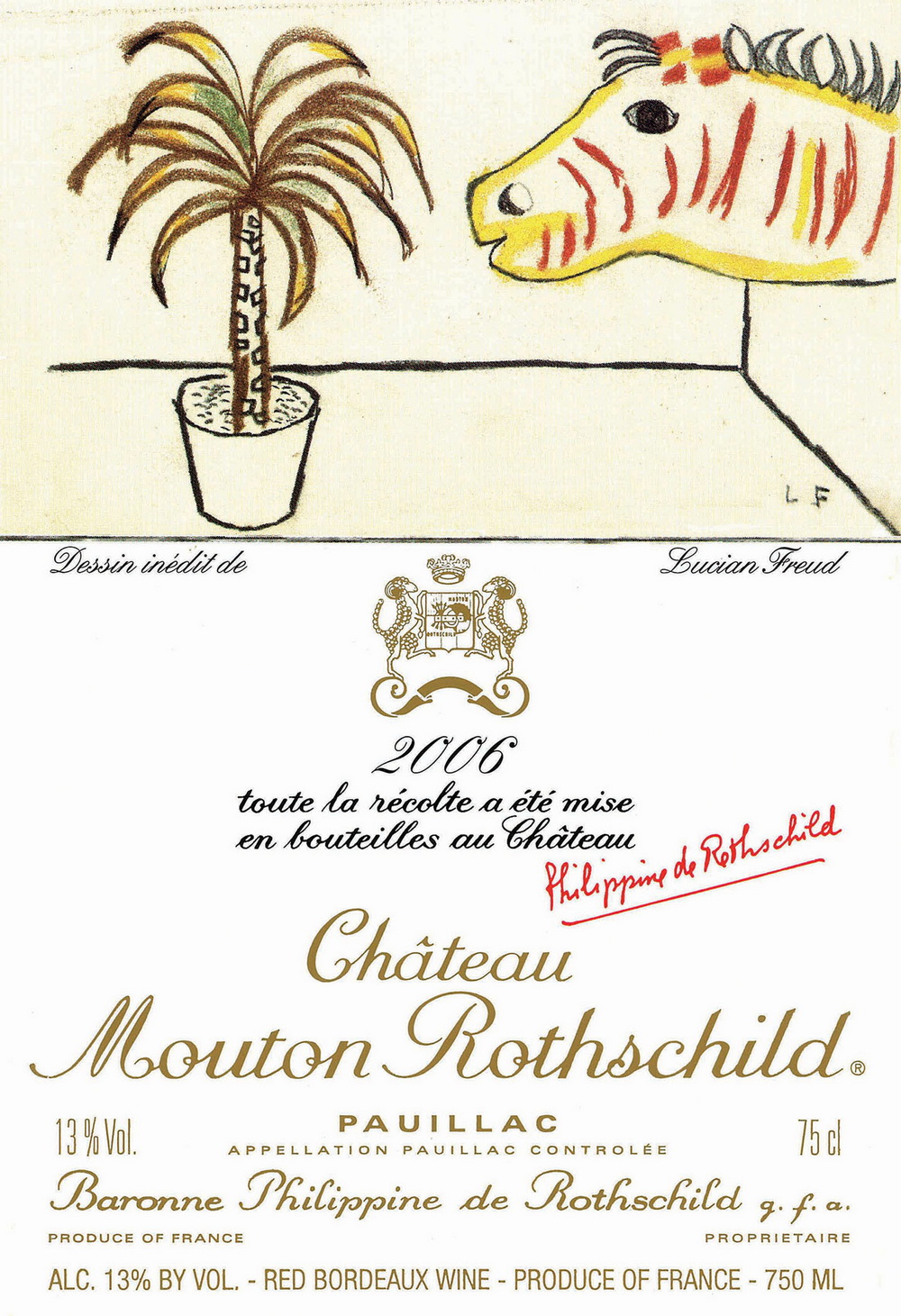

A recent decision by New Zealand’s intellectual property office to strike down Chateau Mouton-Rotchshild’s complaint that the wine name “Flying Mouton” infringed its trademark highlighted one of my big beefs with modern wine brands.

Flying Mouton, a Hawke’s Bay pinot noir made by Osawa Wines, found itself embroiled in a trademark dispute when Mouton-Rothschild’s owner, Baron Philippe de Rothschild, felt the Kiwi brand was playing fast and loose with its brand.

Indeed, the word ‘mouton’ is central to the famous Bordeaux chateau’s heritage and it justifiably wanted to protect it. But the tipping point for the New Zealand authorities was clearly based on the fact ‘mouton’ is, quite conveniently, the French word for sheep.

Okay, so mouton refers to sheep and, as you will know, New Zealand is famous being home to more sheep than human inhabitants. It only stands to reason, then, that if we see the word ‘mouton’ on a wine label we’ll know it’s referring only to the ruminant mammal we all love for soft jumpers and rich cuts of meat, right?

Well, not so fast. Not long ago, we discussed the issue of New World wineries, particularly those from the US, using French words like ‘clos’ or ‘chateau’ in the names of the wines they sell in Europe. The point was that, by using words normally associated with French vineyards, New World producers were more or less copying their Old World counterparts for lack of originality and, perhaps in the worst cases, hoping to gain sales from unsuspecting consumers.

With that in mind, we could say mixing French words on a Kiwi wine label is yet another example of an attempt to co-opt French wine culture rather than adopt a distinctly New World identity.

But it is more complex than that. While Baron Philippe de Rothschild SA might be offended its famous moniker has been co-opted by a New World upstart, the aspect I find truly annoying with many of these wines has nothing to do with the name appearing to be a ripoff of a famous label.

As a seasoned wine drinker, I would find it difficult to create a scenario where a consumer would encounter Flying Mouton and confuse it with the much more expensive Chateau Mouton-Rothschild, although crazier things have happened. So while the New Zealand authorities were right to shoot down the complaint of copyright infringement, no one can forgive the real sins here, and that is the blatant butchering of English idioms in an attempt to develop a catchy brand name and, perhaps worst of all, the creation of yet another critter label in the wine world.

As a seasoned wine drinker, I would find it difficult to create a scenario where a consumer would encounter Flying Mouton and confuse it with the much more expensive Chateau Mouton-Rothschild, although crazier things have happened. So while the New Zealand authorities were right to shoot down the complaint of copyright infringement, no one can forgive the real sins here, and that is the blatant butchering of English idioms in an attempt to develop a catchy brand name and, perhaps worst of all, the creation of yet another critter label in the wine world.

First up, the butchering of the famous English idiom of impossibility, “When pigs fly.”

Think about this for a moment. Flying Mouton. Flying sheep. Have you ever heard the phrase, “When sheep fly?”

Never, that’s when. And that’s the rub. It is neither a familiar idiom we all understand, nor does it make you smile momentarily the way South Africa’s ‘Goats do Roam’ did when you thought no one was looking. And you did smile when you first saw the Goats do Roam label, because I did and everyone else around me did as well (and then those smiles melted away the instant the wine touched our lips).

This brings me to the second offence. Critter labels. Back in 2006 a NewYorkTimes article reported that market research company ACNielson found that of the 438 table wines had been launched in the in the previous three years, a whopping 18 per cent featured an animal on the label. Back then, the market for critter labelled wines was worth at least $600m.

More recently, a study by Unity Marketing released at the beginning of this year found people were more likely to buy wine because it created familiarity that likely drew customers back.

As Pam Danziger, president of Unity Marketing said,

“These labels create unexpected and memorable connections between the consumer’s perception of the image and their identification of the wine. Consumers find it easier to process an image if they have already viewed the image in another context or if they associate the image with something in their personal lives.”

In other words, if the brand stands out and people see a cute, cuddly creature on the bottle, they are likely to buy it again and again, even if the actual wine is, to be diplomatic, anything but a stand-out.

Sure, there are critter label wines that are indeed very good, such as Frog’s Leap, Duckhorn Vineyards and the like, just as there are classified Bordeaux chateaux that fall short of their expected quality levels. With everything, there is always the exception to the rule.

So there we have it. Two mortal sins committed on a single wine label. A butchered idiom and a cute, furry critter. Creating a strong brand and a unique identity is one thing, but I can’t help but feel Osawa fell wide of the mark when it used French words on its label when it is based in country that isn’t even remotely Gallic.